Let’s imagine that you’re a middle school student.

It’s the first day of school, and you walk through the crowded hallways into your science class. But you’re shocked to find yellow CAUTION tape blocking off part of the room. “What happened here?” your new science teacher asks.

Katie Sosnovik, Mount Olive Middle School, NJ

Welcome to The Nature of Science, a Mosa Mack Science unit that challenges students to think like a scientist in order to crack “The Mystery of the Pilfered Popcorn” case. In this investigation, students wonder, question, collect evidence, analyze data, and draw conclusions. In other words, they learn – through doing – what science is all about. And that’s what makes The Nature of Science the perfect introductory unit to start the school year.

This strategy may elicit some skepticism. Is it too early to launch kids straight into an investigation? Shouldn’t I start in a more traditional way? Will I lose control of the class?

We’ve been there. When teachers on the Mosa Mack Science Curriculum Team began using “crime scene investigations” to introduce the study of science in our own classrooms, we shared these initial hesitations. But year after year, these investigations have proven to be an overwhelming success, which led us to adapt one into a full Mosa Mack unit for our community.

Teachers can print “The Mystery of the Pilfered Popcorn” as a comic book and/or view the motion comic, then use our Evidence Packet and instructions to stage the live crime scene.

In this blog, we explain why the mystery is not just a fun and exciting entry to science, but also a pedagogically sound one. This unit introduces four key Scientific and Engineering Practices (SEPs) that every scientist must become proficient at. Let’s break down each one:

1. Asking Questions and Defining a Problem

“Who stole the popcorn?”

Putting students face-to-face with a live, unsolved mystery immediately tells them that they won’t just be sitting and receiving information in science class. Instead, they’ll be actively participating, observing, and asking questions.

Students first study the crime scene and point out possible clues: footprints, fingerprints, hair samples, and a handwritten note. These discoveries help them articulate the problem to be solved: The popcorn has been pilfered and we need to identify the culprit.

Students find meaning in raw observations by generating questions: “What might each of these clues tell us about who the thief is?” This helps them define sub-challenges that they’ll tackle along the way (e.g. identifying suspect hair color and type).

Throughout the investigation, students are encouraged to think critically about their assumptions and to refine their questions and definition of the problem—skills all scientists practice during field and lab research.

2. Investigating and Testing Evidence

Students carefully gather a variety of evidence from the crime scene and then analyze and test it. They obtain fingerprints, perform ink chromatography, study microscopic views of hair samples, and measure shoe print sizes.

By using methods and tools of actual criminologists (from evidence markers to suspect profiles), students come to appreciate how science and scientific thinking are central to real-world problem solving.

3. Collecting and Analyzing Data

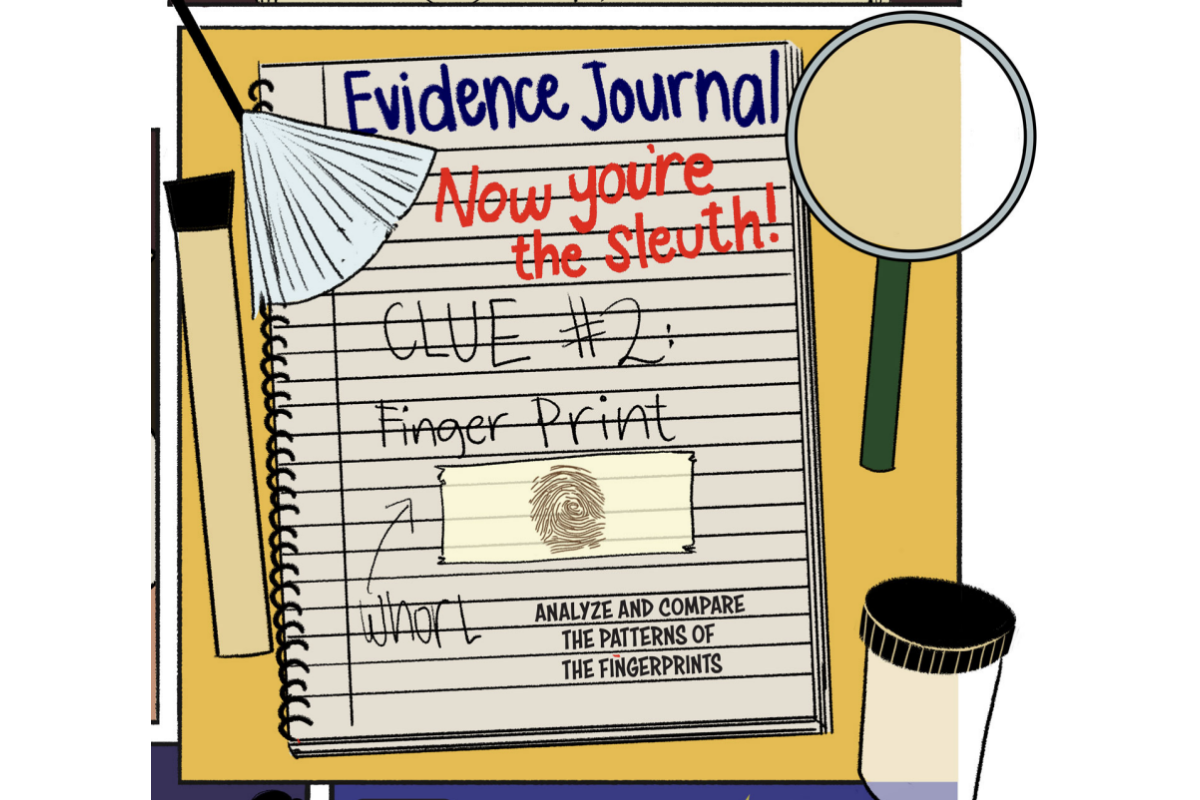

The characters in the animated mystery use an Evidence Journal to compile and analyze their data. In a live in-classroom crime scene investigation, students can follow this model to create their own journal. This activity reinforces the importance of organizing data in order to effectively interpret it.

As students test and observe evidence, they

-

- Complete data tables to look for trends and correlations.

-

- Compare crime scene fingerprints and hair samples with common fingerprint patterns and hair follicle charts; study and compare ink patterns; check shoe print size against a shoe print-height correlation chart.

-

- Compare all their evidence with clues gathered from various suspects.

This process equips them to develop and refine hypotheses about who can be ruled out and who the culprit may be—a case study in how much more we can learn from data by analyzing it in wider contexts.

4. Constructing Explanations and Conclusions

The “whodunnit moment” is the most exciting part of any mystery. But as the student-detectives learn in this investigation, scientific claims or explanations must be founded on and consistent with the evidence.

While identifying who they think is the thief, students must recap the clues in a forensic report, identifying and describing all the supporting evidence they’ve collected. They must also describe how that evidence supports their claim. We call this process CESR—claim, evidence, scientific thinking, and reasoning—and you can learn more about it here.

A crime mystery exemplifies the process of every scientific pursuit. We begin “in the dark” with many unknowns. But through systematic observation and analysis, we inch closer and closer to clarity and conclusion. That’s an adventure every science student will fall in love with.

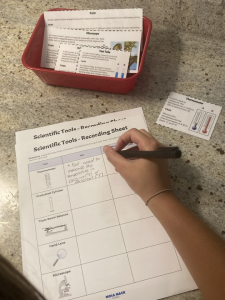

Bonus Activity: Introducing Scientific Tools

But wait – there’s more! The popcorn investigation features a variety of common scientific tools and practices which students will need to understand and use throughout their scientific education. To help with that process, we have developed a downloadable task card activity that can be paired with the mystery. Once completed, students can add these cards to their lab notebooks to look back on throughout the year.

APPENDIX:

Next Generation Science Standards: Scientific and Engineering Practices

Leave a Reply