How Science Educators Can Support English Language Arts Skill-Building

There are important initiatives going on in ELA, Math, and Social Emotional Learning classrooms right now and, as a result, science is often unintentionally sidelined. But science can be the perfect place to naturally support those initiatives.

Over the next three months, this blog series will explore how science can reinforce the content and skill-building within these other three disciplines.

Let’s start with Science and ELA.

ELA educators have reported that their students struggle most with three specific skills. And as it turns out, those same three skills are essential in science, too.

1. Procedural and Evidence-Based Writing

Disorganized writing is the number one issue reported by ELA teachers. Students have trouble ordering and connecting their points and ideas into a coherent beginning-to-end structure.

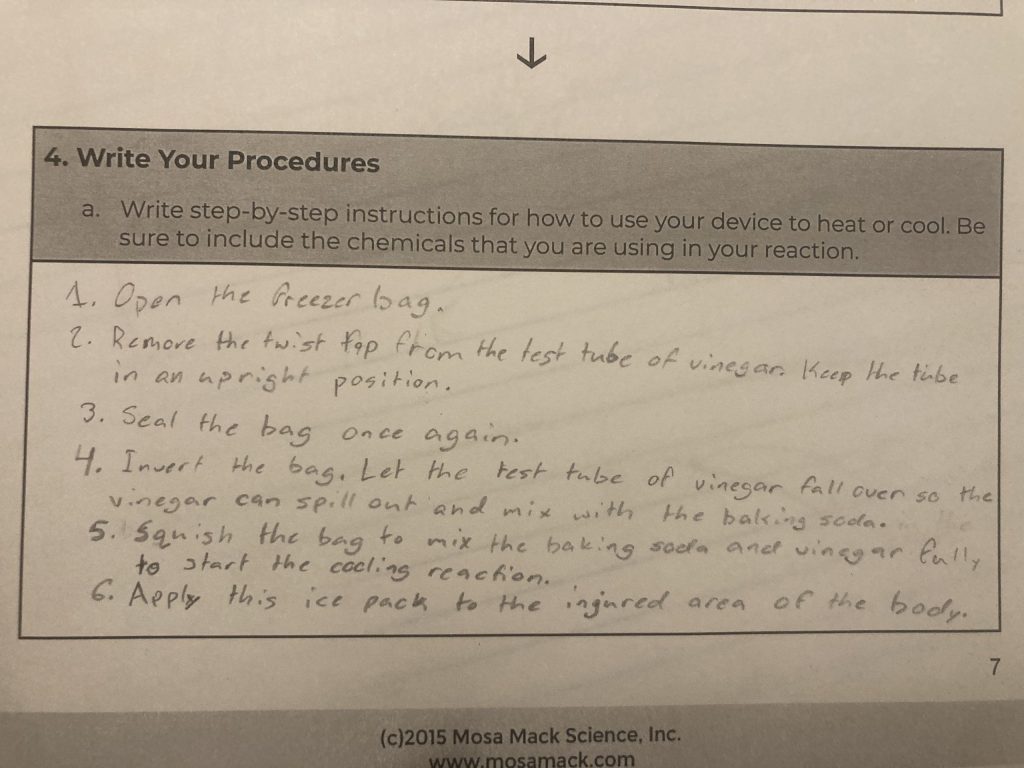

Fortunately, science class can offer them a great way to improve this skill with procedural writing, which science teachers can infuse into every unit, from lab investigations to engineering challenges. With consistent modeling and guidance from teachers, science students learn how to write clear and specific directions that they and their classmates then follow to carry out tests and experiments. Through this hands-on trial-and-error process (and plenty of hilarious miscommunications), students get better at ordered writing as well as providing the necessary levels of detail and language specificity.

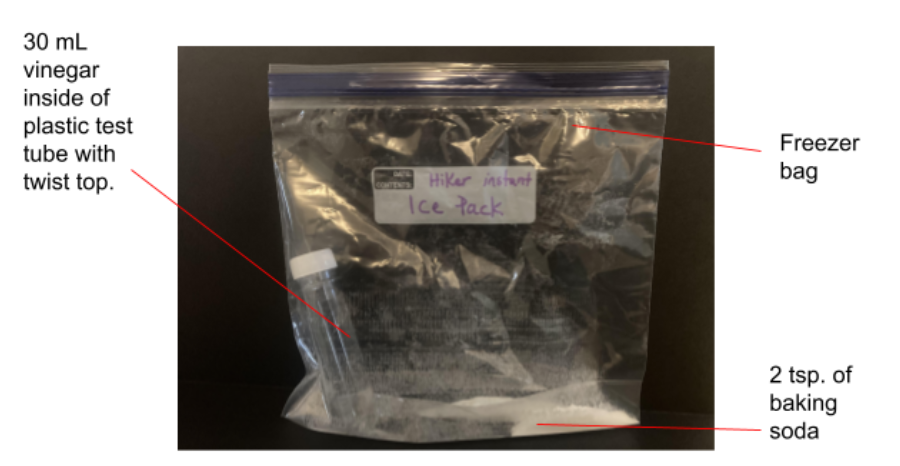

In this engineering challenge, for example, students are tasked with designing and testing a portable heating or cooling pack, then writing out their procedure for someone else to recreate their design.

In ELA, teachers can bring their own lessons in procedural writing alive by incorporating this collaborative, hands-on approach. Writing travel directions, recipes, game rules, and equipment manuals can all yield a much deeper learning experience when students are challenged to also carry out the procedures they develop.

Science and ELA teachers can reinforce this learning together by spotlighting the common elements in all procedural writing: purpose, materials, steps, and conclusion. There are also unlimited opportunities for colleagues to develop cross-disciplinary writing exercises together and coordinate them between classrooms.

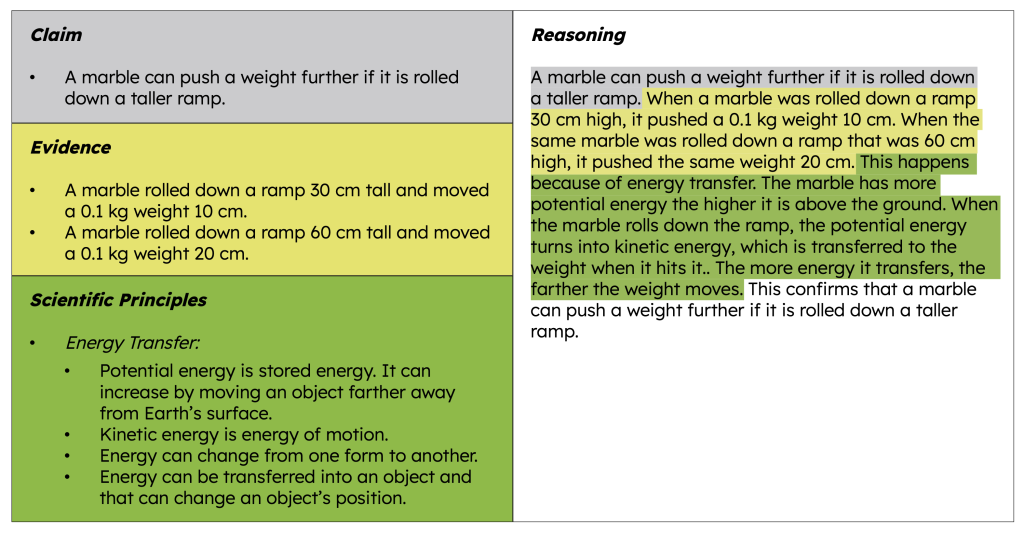

Similarly, science and ELA share an emphasis on evidence-based writing, both of which help students to organize their writing. Science courses often begin with a Claim-Evidence-Reasoning unit specifically devoted to this skill, which is then practiced in everything from creating lab report conclusions to science fair presentations. Students learn how to identify claims, evidence, and reasoning; how to write their own reasoning statements by combining all of these pieces; and how to “check their own work” by identifying the parts of their reasoning using a color-coding system.

This approach works just as well in ELA. Though ELA teachers might use the term “argument” instead of “claim,” or they may employ a different framework such as RACES (Restate, Answer, Cite, Explain, Summarize), the underlying concepts and structure are largely the same. By explicitly pointing out this overlap, science and ELA teachers can help students connect the dots for what they are learning in separate classrooms to develop a fuller, interconnected experience.

2. Breaking Down Nonfiction Texts

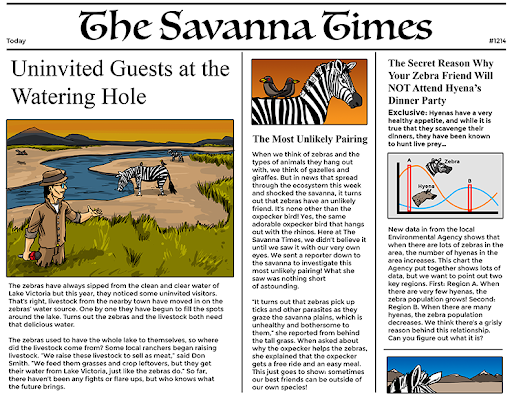

ELA teachers also report that their students struggle to break down dense nonfiction texts including textbook passages, newspaper stories, and test excerpts for analysis questions. They specifically have trouble identifying text features and structures (titles, subheadings,

captions, etc.), largely because they have limited exposure to high-quality nonfiction texts.

Meanwhile, more and more science educators are integrating a variety of nonfiction texts—from science journal reports to magazine articles—as part of a widespread push to emphasize the real-world relevance of science. This presents a natural opportunity for ELA and science collaboration.

For example, science teachers can integrate and emphasize specific ELA concepts to help students break down scientific texts: cause and effect, sequence, main idea and details, problem/solution, etc. Even the occasional use of ELA-specific questions in a science context can be a great reinforcement technique, like asking “which diagram in this text helped us answer this question?”

ELA teachers can then use these same scientific journal reports or articles to identify and analyze the components, from strategically placed headings to bullet points, diagrams, and labels.

Since access to high-quality nonfiction texts is a common concern for ELA teachers, science teachers (and administrators) can take a proactive role by sharing science reading resources with their ELA colleagues. If science and ELA teachers coordinate their lessons, imagine the confidence and connections students would draw when going over the same text in one class and then another.

3. Vocabulary Development

The third issue reported by ELA educators is that students are memorizing vocabulary instead of internalizing the meaning. This makes it difficult for them to apply those words to other contexts. Luckily, layered vocabulary application is a central focus of the Next Generation Science Standards, which more and more science curricula are adopting. This includes both tier 3 context-specific vocabulary (such as gravity and friction), as well as tier-2 words (which are high-frequency vocabulary words used across subjects, such as motion and force).

In science, the best practice for vocabulary is to only provide definitions at the end of the lesson. This technique allows the students to construct the meaning first before connecting it with the term, which is a practice that is easily adaptable for ELA vocabulary lessons as well.

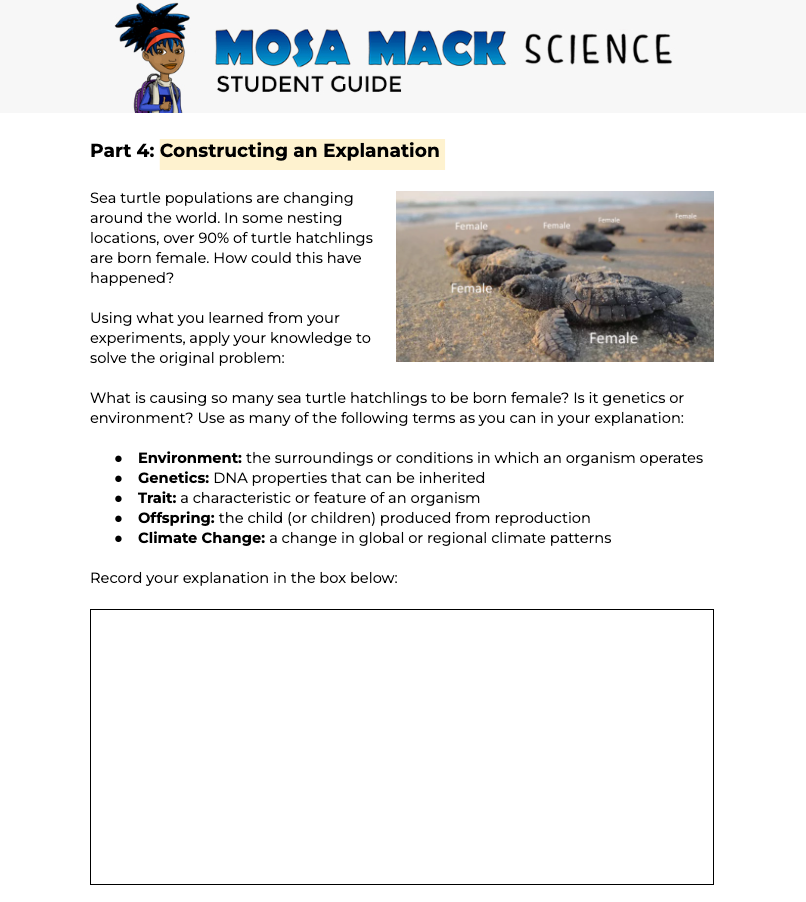

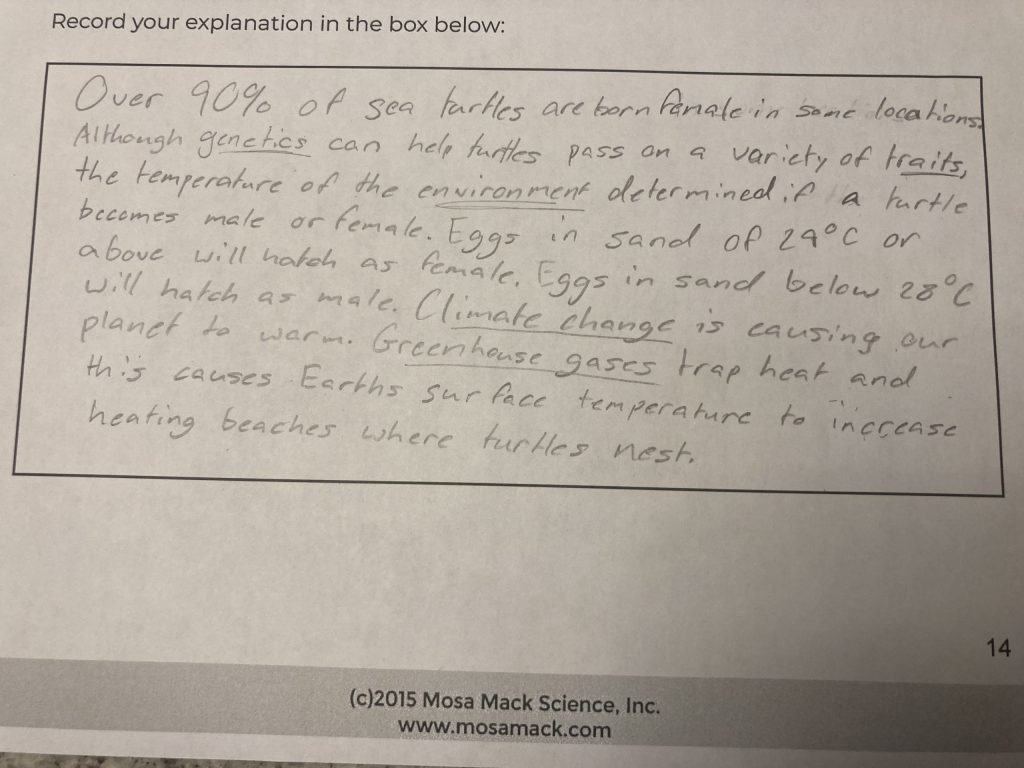

Science teachers can also work to spiral vocabulary throughout their units and discussions. This gives students exposure to vocabulary in context, through hands-on exploration, touching and feeling the terms in a lab setting, and the applying that vocabulary throughout the rest of the unit. In this example – students construct meaning through the application of vocabulary to describe what they have just experienced in a genetics activity.

Actively incorporating resources like vocabulary mind maps is another great way for science teachers to support ELA by allowing students to connect vocabulary terms to visual diagrams.

For More Guidance

Beyond these three areas of learning, there are countless more ways that science can support ELA. For more guidance, review the bottom of each Next Generation Science Standard, where you’ll find a section called “Connections: ELA and Literacy” that specifies all the relevant ELA standards for that science standard. This is a fantastic tool to help science educators focus their teaching around ELA goals and brainstorm opportunities for cross-discipline collaboration.

Above all, communication between science and ELA educators will make these strategies most effective. In-depth co-planning is always ideal, but even a quick chat or email exchange will go a long way. “This is what we’re working on in our classroom—any opportunity to enhance this in yours?”

Download the One Pager

You can download our Cheat Sheet of all these tips below to help keep them top of mind when planning and collaborating. It could be the launching board for a rich discussion amongst grade-level teams and school leaders.